Goldbrick Hill

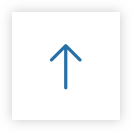

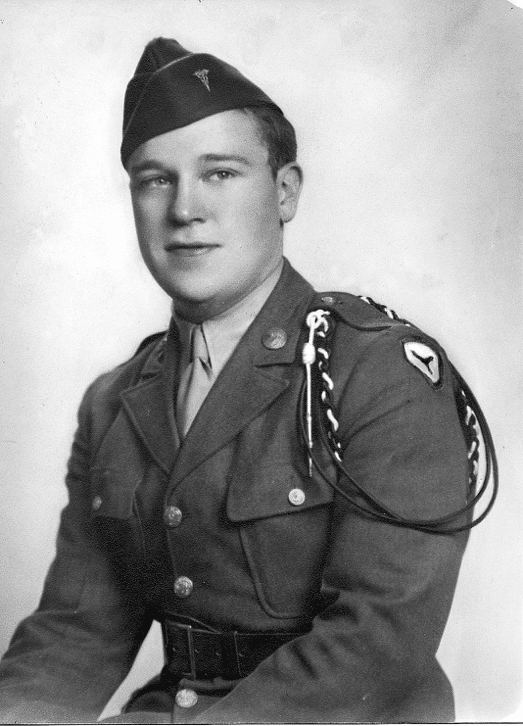

A Memoir by Glenn Doman K Company, 346th Infantry Regiment

Company Commander Glenn Doman

This week marks 75 years since the liberation of Auschwitz Concentration Camp. The liberation of many other concentration camps followed with the successful conclusion of The Battle of the Bulge and the destruction of the Siegfried Line. Glenn was be part of that liberation. As part of the centennial celebration of his life and in tribute to those who lost their lives by his side we reprint his own account of one battle from early March 1945.

Immediately following the Battle of the Bulge my division, the 87th, had plunged far into the Siegfried Line. We had outrun our supplies and the totally ruined roads of Belgium and Germany did not permit our adequate resupply. We were, therefore, in a comparatively quiet position and I was able to leave my company for a ten-day tour with the Air Corps, a thing which I would not have been able to do had the situation been an active one. An infantry unit commander does not leave his men while they are in a bad position, not if he wants any of them to go with him on his next attack.

After ten interesting days and five bombing missions with the Air Corps, during which time I had no word of my unit, I returned to the town in Germany where division headquarters was headquartered. I presumed that the station was as static and quiet as it had been when I left and therefore looked forward to a comfortable night, in a comfortable bed, in a comfortable house, in a comfortable safe town occupied by Division Headquarters. As the kids say today “I was a dreamer.” I pulled into Roth and first met Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis, my battalion commander. He had just returned to his battalion after four months in the hospital with an extremely nasty chest wound. We greeted each other with a deep affection peculiar to infantrymen in combat.

The world famous Alamo in Texas where the garrison was slaughtered by Santa Anna stands today as a monument to that garrison. The garrison was commanded at that time by Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis. You will remember that drawing his saber he cut a line in the courtyard of the Alamo, asking those who would defend it to the death to step across. Every man in the garrison stepped across, headed by the Texas hero, Davy Crockett. To a man they died defending the Alamo. That Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis was the great-grandfather of Lt. Col. William Barrett Travis, who I was at the moment greeting so warmly.

My plans for the comfortable night went up in smoke, as I talked with Col. Travis. The battalion and my company were in serious trouble. In the preceding two days we had advanced one thousand yards against our long time enemies, the vaunted 6th SS Mountain Division. That advance had been a costly one.

I had left the company in command of 1st Lt. Carl Lee. Lee was gone. I had left Lt. Pieper commanding the 2nd Platoon. Pieper was dead. The new Lt. named North had come to my company during my absence. I never saw North. He had been killed the day before. Sgt. Crowley and Sgt. Cramer were two of the finest lead scouts in the United States Army, and both of them had been hit by the same blast. Sgt. Inzer was dead. So were many others. I belonged with my company and right now Col. Travis and I hastened toward the sounds of war to our front.

When shells were landing nearby we left the jeep and ran to the battalion command post located inside a filthy German pillbox, recently vacated by the Supermen. Col. Travis quickly showed me on the map the path to my company, which led up a great hill thickly covered with woods and at the moment thickly covered with Jerry Mortar fire.

As I dashed from cover to cover along the path, I saw everywhere about me the evidence of yesterday’s battle. Dead Germans in quantity lay where they had fallen defending this battle-scarred hill. Here and there lay one of our boys not as yet reached by the graves’ registration people. The company was under the command of 2nd Lt. Morrow, a recent infantry officer made over from an artilleryman. Knowing nothing of infantry methods, I had felt grave doubts about him when I left for the Air Corps. My fears were unfounded. Many of the dead Germans I had seen on the way up the hill were specimens of his remarkable leadership. I learned later that leading the company up that hill he had run out of carbine ammunition. He had broken his carbine over the head of a German soldier and then brandishing his entrenching tool he had led the company up that hill and successfully taken it.

I have had the honor of being decorated by the Duchess of Luxembourg, Lord Imber Chapel, the British Ambassador to the United States, and by General Patton himself, but I shall always consider that the greatest triumph of my life and my greatest tribute is that I received the warmest welcome upon reaching my company, which was composed of a series of foxholes on top of the hill so recently captured. I remember, with no shame, having to brush tears from my eyes when my people were so sincerely delighted at my return.

Shelling of our position continued very heavy until night fall, at which time we captured a German patrol led by a captain, who walked into our position while trying to locate it. At midnight I was informed by radio that I was to report to the battalion commander for an attack order. I took the prisoners back with me for questioning. The attack order which we received was a grim one. A widespread assault on a broad front had been ordered by the Third Army. Immediately to our front lay an ominous hill. The map called it Gold “B” Hill. Of course it immediately became Gold Brick Hill to the soldiers.

Gold Brick Hill was 700 yards from the bottom to the top. It was completely devoid of the slightest cover and on its top were seven pillboxes with eight-foot-thick concrete walls. The pillboxes were mutually supporting and the hill commanded the entire front.

Gold Brick Hill had to be completely neutralized before my division and the Third Army could advance. The German captain, under some pressure, talked. In the seven pillboxes were 200 crack German troops and seven officers. Gold Brick Hill, he boasted, would never be captured by direct assault. It could only be captured by being surrounded and its defenders starved out. This process he estimated would take two months, if we get around Gold Brick Hill, which we could not. To add to the difficulty a light snow had begun to fall, which would silhouette and outline us, making us beautiful targets.

The battalion was far under strength. My company, normally composed of 187 men and 6 officers, now had 30 men. I Company had 35. L Company 50. These were the rifle companies of the Third Battalion. The order was unfortunately quite definite. It said that the Third Battalion would seize and hold Gold Brick Hill. It did not say “if possible.” The colonel gave us his attack order. There would be a ten-minute artillery preparation starting at 0300. Company I on the right and Company K, my company, on the left would cross the line of departure, a woods at the foot of Gold Brick Hill, at 0105 while the artillery was still firing. We would be preceded by five tanks.

This announcement was met with sarcastic laughter. All our experiences with the tanks did not lead us to believe that they would attack. The colonel assured us they would not run away. As we approached the top of the hill the artillery would lift and we would take their position.

With a heavy heart I returned to my waiting company headquarters and platoon leaders. The accomplishment of this job seemed virtually impossible, but the orders were quite clear. We would seize and hold Gold Brick Hill. No one said “or die trying.” That we understood.

I tried to keep my voice steady as I gave my attack order. When a company attacks it maintains one of its three rifle platoons and its weapon platoon in reserve. My entire Company, cooks, clerks and all had less than one platoon. If by any turn of fate we took this position it would have to be by an all-out effort and ignoring many of the basic laws of the military. We would attack cooks and all, without any reserves, on a 200-yard front. Every weapon in the company would be fired at the pillboxes, as fast as they could be fired. The B.A.R.s would fire 200 yards to the front. Riflemen 100 yards, to the front. The light machine guns, in movie fashion, would be fired from the hip and while moving. The rocket launchers (bazookas) would fire directly on the pillboxes.

The roar of an infantry bazooka round is difficult to tell from an artillery round. We hoped that the Germans would never know when the artillery stopped firing. Men armed only with a pistol would fire the pistol 50 yards to the front. Everybody would shoot low and fire whether or not targets appeared. We would try to get ricochets, which when coming in your direction sound extremely dangerous. We hoped they would sound that way to the Germans. The one consolation was that we would have the cover of five tanks in front of us.

We slipped through the woods at five minutes before one, arriving at the edge of the woods, which was our line of departure. Covered by trees we heard our artillery give the message “on the say” and soon fierce firing landed on the hill to our front. I looked at Gold Brick Hill and had a sinking sensation. It was worse than I had pictured it.

While the artillery prevented the meatheads from leaving their pillboxes, it could do no harm whatsoever to the Germans inside. I was somewhat surprised to hear the tanks moving out of the road that led to our position and was cheered by the fact that they did. In front of us the tanks fanned out and started up the hill. I stood up and waited to give the signal to move out. As I did the tanks turned and came back down the hill. In all honesty I admit I was delighted. Now of course we would not be expected to attack. The tanks were leaving. The colonel came running toward the position, swearing violently at the tanks and threatening to shoot the tank commander at sight. Grimly he told me to move out quickly in the attack before the artillery stopped firing. My stomach did flip-flops.

“Colonel, it is impossible, you know we cannot…”

The colonel swore, “I said move out.” He meant it. My mind raced.

Surely, surely no soldier would go up that hill. Getting killed is bad enough, but getting killed while accomplishing nothing was useless. I loved and admired my company, but I had no right to expect they would go up that hill. In a few seconds a thousand thoughts raced through my mind. To explain them is extremely difficult, perhaps embarrassing. I hope you will try to understand how I felt. My men were excellent soldiers, the very best, but nobody had any right to expect them to go up that hill. They were there because it was their job, but few of them had asked to be there. Somebody else had made this war; they were simply fighting it.

To this day I am firmly convinced that if I were a private no one could have gotten me out of that woods. I think perhaps I am not a very brave man, but I did not enjoy the same immunity these soldiers enjoyed. This was my war. I had asked for it. Even sought it. I wanted to wear pink pants, be called “Sir,” eat in the Officer’s Mess, sleep in the Officer’s Quarters and be saluted. I had asked for this. Deep in the heart of every infantry officer lies the realization that some day he may have to pay for all these privileges. He may have to pay with his life and for nothing at all except as a symbol. He realizes that this probably won’t happen, but he also realizes that it can happen and if faced with this eventuality he must accept it, or loose the right to live at peace with himself. I was now in this position.

I did not expect the men to go and I did not blame them a bit. I agreed with them but that was it. The men were watching me for orders. I waved my arm forward and tried to pretend that I expected them to come. Scared almost motionless I walked out of the woods. My only hope was that the Germans would fire quickly and wound me while I was close enough so that the men could drag me back into the woods. When I was ten yards out of the woods I stole a glance to my right where I Company was supposed to be attacking on line with us. I saw one man, Captain Swanson, commander of I Company. My heart sank further. I would have given all that I possessed to look back over my shoulder, but if the men were foolish enough to come, my looking back would show them that I did not expect them to.

When I was twenty yards up the hill and praying to be hit now, but only a little bit, I heard behind me a commotion I shall never forget. They were there, every single one. They were firing as fast as they could fire, exactly as the orders said. I looked back. I shall never forget that moment. My heart soared. These were my people and in my mind’s eye I shall see them always as they come shooting from that woods. Scared, cold, tired, even exhausted, and they came shooting. I was never happier. It almost didn’t matter if I got hit. This surely was the supreme moment for me. My boys were coming with me.

By the time we were halfway up the hill the men were charging wildly, screaming and firing. I have often thought that if that scene were made a moving picture, every soldier who saw it would laugh in disbelief. It just didn’t seem possible.

As I went over the crest of the hill there was before me a German soldier outside a pillbox. In his right hand he held a rifle, on the muzzle was a white handkerchief, on the open palm of his other hand was a pistol which he held toward me as a souvenir. He had heard about the Americans. At my side was a little soldier, who could not have been over 5’2″, aimed at the German; 10′ away he had a bazooka. Had he fired it at that range we would all have been destroyed. I shouted to the German, he dropped the weapons and ran into the pillbox behind him. He led 22 Germans out of that pillbox.

With disbelief my messenger and I entered the pillbox. On a table a telephone was ringing. My messenger, Henry Simons, was a German Jew. His mother and father had been in Dachau. His grandmother and grandfather were still in Buchenwald. He had come to the United States when he was sixteen. Now at eighteen he was back in Germany, having volunteered for Rifle Company. Henry knew why he was fighting the war.

He answered the telephone. It was the German commander in Pillbox #3 wanting to know how we were doing. In flawless German, Hank told him we were doing very well and that he had better get out of the pillbox with his hands up very quickly. That news was something of a blow to him. He replied that they would never surrender, never.

We went out and over the hill toward his pillbox. All of the others had quickly fallen to my soldiers and I Company, which had also attacked just as fiercely. We were met with a blast of machine gun fire from the German Command Base. We fired bazookas at the pillbox, but did it no harm.

We had arrived at a stalemate which could go on indefinitely. We went back and phoned again to the German commander. He assured me that they would never come out, never. I agreed that that was perfectly all right with me if that was the way he wanted it. I would even help him have his way. To make it positive I would bring up bulldozers and cover up the pillbox, and he could stay there with the rest of his officers forever and I hoped his coffin was comfortable. I gave him thirty seconds to think about it. He did. He came out.

Realizing the position was taken, the German artillery, without regard for the German prisoners, fell heavily on our position. We got inside the pillboxes and called for casualty reports from my officers and I Company. The news was too good to be true. We had captured seven pillboxes, 200 Germans, six officers, and killed many. Neither I Company nor K Company had a single solitary casualty. No one had even been scratched.

War is an emotional time. I felt my eyes blur again. I was totally ashamed that I had ever doubted these men of mine. I felt that I did not deserve to be their leader. This I knew, were we ordered to assault the gates of Hell itself, these American infantryman would go. We had seized and were holding Gold Brick Hill. The 87th Division pressed onward. Much later my division commander, Major General Culin, said this to me. I have always considered it the supreme accolade my company received. “Doman,” he said, “Tell K Company this for me. I have been a soldier for 35 years. Hundreds of times in those 35 years I have wondered why. Now I know. I stood on Hill 29 and watched the attack on Gold Brick Hill. My 35 years in the Army were spent waiting for that attack. If I had a picture of those men going up that hill, I should carry it in my pocket forever and bury it with me. That attack was complete compensation for the past 35 years.”

The Third Army had a historian who was charged with the responsibility of recording its day-by-day record. No one can hope to record in detail the actions of all the units of the Third Army, for it was a representative battle by a small unit of the Third Army so recorded daily as typical of the actions of the Army. Weeks later I went back to Gold Brick Hill with the historian who was sent by General Patton to record the Battle of Gold Brick Hill as the history of the Third Army for that day. I went over the ground foot by foot and recorded the conversations, word for word that took place.

Some day what these men did will be officially recorded for all to see. Some day in the future I shall return to Gold Brick Hill. No doubt the pillbox will be overgrown with weeds, while only here and there a German gas mask will lie rusting, to indicate that on this spot I Company and K Company of the 346th Infantry fought a battle, but as I stand on that hill and look back towards the woods I shall see them as clearly as I saw them then and see them now, and just as surely a gust of wind will blow a speck into both of my eyes.

Better Times: Glenn with his son, Bruce who was born a year after the war ended

Donate

Donate