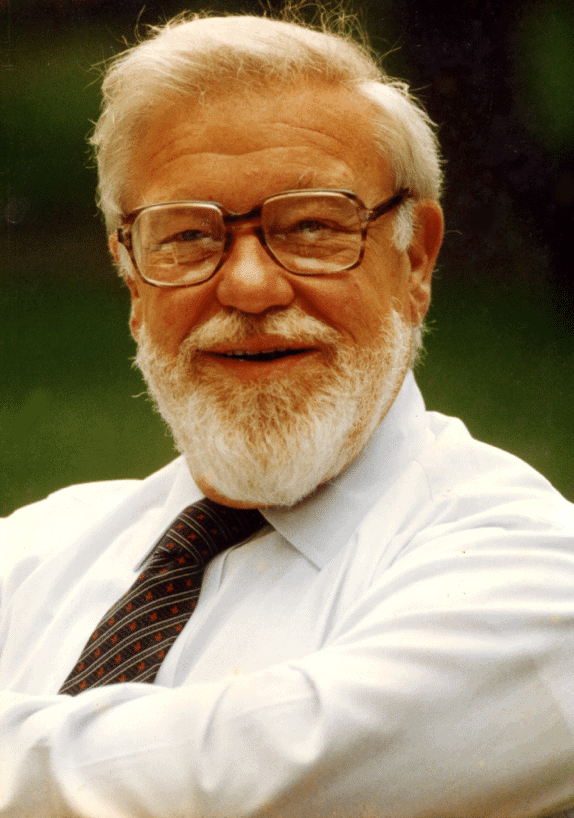

A Tribute to Glenn J. Doman

GLENN J. DOMAN

Glenn had enormous energy and contagious enthusiasm. He understood how ugly and violent and insane the world could be but his optimism never wavered. He was determined to create a better world for parents and their children.

Glenn was a pioneer in everything he did – a leader in his field, an innovator, and an iconoclast. He was prepared to fight for what he believed was right for brain-injured children and well children. Along the way, he encountered resistance, even ridicule, but that never deterred him from his intention to fight for the right of every brain-injured child to be well and every well child to be better.

Glenn’s fighting spirit was evident from the start. Born 26 August 1919, in Hilltown, Pennsylvania, he was the eldest of three children of Joseph H. and Helen (Gould) Doman. “I was raised in a home where there was a great deal of love, ” Glenn said in a 1963 interview with Pearl LeWinn. “It was definitely a kid-oriented home, and I guess because I was the first, I was the most spoiled. I was a child of the Depression, but I never felt deprived.”

Robert Doman, Helen Doman and Glenn Doman

As a boy Glenn enjoyed nature, and at one point he considered becoming a forester. He joined the Boy Scouts, which, he said, aside from his parents, was the greatest influence on his young life. “I think primarily it taught me ethics,” he explained, and like his experiences later in the military, the Scouts “had a feeling of comradeship and decency and respect for your fellow man.”

Glenn, boy scout on Treasure Island

He continued to live in a world of adventure by reading all of the Horatio Alger books. “I read them all before I appreciated what they had in common, which is that the good guys always won and the bad guys always lost. They were also books about ethics and decency.”

As much as he enjoyed reading, he was not so enamored with school. “The teachers told me ‘sit down, shut up, look at me, and pay attention.’ I had to do the first three, but no one could command my attention. The only way I managed to save my sanity was to let my imagination take me out of that drab schoolroom and away from those teachers. On the wings of my mind I travelled across stranger seas, taller mountains, deeper jungles and hotter deserts than had ever before been seen.

“I spent my days in far off places interrupted by moments of sheer terror when I heard my name called to answer a question. It wasn’t so much that I didn’t know the answer. The problem was simply that I didn’t know the question.”

In high school he occasionally found a teacher who would inspire him to learn. “The sad part of that,” said Glenn, “is that the several decent teachers I had proved that what should have been the rule was only the exception.”

But when Glenn began studies at Drexel Institute and the School of Physical Therapy of the University of Pennsylvania, he was motivated to learn and do well. There he met Samuel Milton Henshaw, the head of the Department of Physiotherapy. “He always gave me a very hard time while I was a student,” Glenn recalled, “but I admired him for the fine gentleman and excellent teacher he was, and I had a great respect for him.” In 1940 Glenn graduated at the head of his class, and Mr. Henshaw invited him to become his first assistant at Delaware County Hospital. In 1941, Glenn was appointed assistant chief of the Physical Therapy Department at Temple University Hospital. Among his other duties was teaching physical therapy to the medical students.

“Fortunately for me and for my future there was a man at Temple who knew more about brain-injured children than any man alive,” said Glenn. “His name was Temple Fay and he occupied both the Chairs of Neurology and Neurosurgery of the Medical School. I was fascinated by all that went on in the hospital. I was aware of my monumental ignorance, and it was usual for me to spend my off hours in the evenings going everywhere in the hospital. On one particular evening I was in the nursery where very small, very sick children were kept. I shall never forget my first sight of a severely involved child. He was an eleven-year old-hydrocephalic. No one in pediatrics or neurology had ever taught me that such children existed.

“Although today, many thousands of brain-injured children later, I can honestly say that while I have never once since felt horror at contact with a brain-injured child and am, in point of fact, quite upset by people who do, I must admit that I strove mightily to contain the horror that I felt then.”

Glenn had the audacity to go to Dr. Fay’s office and ask to see him, and surprisingly he did. After a number of questions about the child he had seen, Dr. Fay invited Glenn to watch him operate.

“That this magnificent surgeon, this unbelievably superb teacher, should have allowed me into the operating room to observe him was one of the greatest happenings of my life.”

Glenn explained, “In the sixteen years of hours, days, weeks, and months that followed, when for weeks on end I virtually lived with Fay, I do not believe there was a period of longer than fifteen consecutive minutes that he was not teaching me – and he was a superb teacher.”

To the surprise of the nation, Pearl Harbor was attacked on 7 December 1941, and the United States entered World War II. On that day Glenn enlisted in the army as a private in the medical corps.

For thousands of parents around the world, Glenn Doman is remembered as a hero for his lifetime of search and discovery in the field of child brain development and the gentle revolution he created to provide intellectual, physical and social excellence for all children.

However, seventy years ago, Glenn was a leader and hero to the men that fought with him on the battlefields of Europe, during the Second World War. As a young Lieutenant, he was an inspiration to the men he led in the 87th Infantry Division in Patton’s Third Army.

A young Sergeant Doman newly enlisted in the medical corps shortly after Pearl Harbor

Glenn emerged from the war as a Lieutenant Colonel, decorated for heroism in action by many nations. He was decorated by the Grand Duchess Charlotte for services to the Duchy of Luxembourg during the Battel of the Bulge. He received the Croix de Guerre of Belgium. King George VI awarded him the British Military Cross – the highest honor awarded in Great Britain to a foreigner. In his own country he was awarded the Bronze Star for heroism in close combat and the Silver Star for gallantry against an armed enemy. He was honored with the second highest military award given by the United States the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in combat, and was nominated by General George Patton for the highest military award, the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Throughout his life Glenn remembered his men with great love and affection. He often spoke of the bravery and humor of his men and their deep devotion to one another. He kept in touch with many of his men and tried to see them at least once a year. He was beloved of the men with whom he fought who were honored to fight beside him.

Their service has not been forgotten. In September Luxembourg celebrated the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Luxembourg. Glenn Doman was honored at the ceremony and a memorial was dedicated to the soldiers of the 87th Infantry Division. Government officials of Luxembourg, U.S. veterans of the World War II, representatives of the US Military and members of the family traveled to Luxembourg to attend the ceremony.

Katie Doman with representatives of the U.S. Marine Corps

Noah, Glenn’s youngest grandson, was asked to speak at the ceremony. He told the audience, “He was truly a soldier for all the people of Luxembourg and the great struggle for the liberation of your beautiful country… and like you, we will never forget.” A U.S. marine was also present at the ceremony and recounted Glenn’s many actions of valor during battle.

Karen and Noah Doman lay flowers at the memorial site

After returning home from the war, Glenn joined the National Guard but he found a new battlefield and enlisted his own team of soldiers to wage war on brain-injury. Glenn and his staff brought hope and help to thousands of parents around the world.

Lieutenant Colonel Doman ten years after the war

Glenn recounted his days as an infantryman saying, “That’s probably one of the strongest experiences a human being can have. It taught me great respect for the American kids of that day, because it is kids who fight the wars, and I’m surprised at how many heroes there are in a small group of people. That taught me a great deal about leadership and appreciation of the people around me. Also, I learned why it was necessary for someone to give orders and necessary for someone to carry them out.”

When Glenn returned from the war, a group of physical therapists helped him to set up a practice, providing him with an office and patients, mostly stroke patients. He married Hazel Katie Massingham, whom he had known since childhood. She was the little sister of his best friend who had grown into a young woman and gained Glenn’s attention. As Katie explained, “Glenn came into my life very early. I think I fell in love with him at age seven, and I have loved him completely ever since. He is the most charming, most vital human being I have ever met.”

Katie was attending the School of Nursing of Abington Hospital and was the first student permitted to marry before graduation. She had trained particularly to be an army nurse, but just as she graduated the war ended.

Katie recalled, “When Glenn was in Officer Candidate Training assigned to various camps in the South he wrote me long, beautiful, fascinating letters, and on the first of each month he sent me gardenias, even when he was in combat. The lovely thing is that ever since, all through our marriage, he has sent me flowers on the first of each month, without fail. When he asked me to marry him he said, ‘I may be a headache, but I’ll never be a bore.’ That has proven to be true.”

Before long Glenn’s practice was growing, and he and Katie were living happily in the suburbs, with a young son. The future seems bright and comfortable. But one day, at a medical convention, Glenn encountered Temple Fay, who once again prodded Glenn’s inquisitive nature. Before long he had agreed to join Fay in his new venture, The Neuro-physical Rehabilitation Center.

Glenn in the early days of The Institutes

Glenn gave up his practice and his office. In return, Glenn said, “Fay made me realize that there was an answer to why my stroke patients rarely walked, often could not talk in a functional way, and absolutely never used their involved thumbs correctly. The reason might exist not in the muscles of the leg, the muscles of the tongue or the muscles of the thumb. Fay taught me to believe that these mysteries might be solved by our understanding how the nervous system worked in a fifty-ton reptile with a three-ounce brain who had been dead for millions of years and whose thunderous tread had not disturbed even the oldest creatures alive today.”

Gradually a team formed, and in 1955 they began The Rehabilitation Center at Philadelphia, with a focus on the rehabilitation of brain-injured individuals. The team included a neurosurgeon (Fay), a physical therapist (Glenn), a nurse (Katie Doman), and a physiatrist (Robert Doman, Glenn’s younger brother). They were joined by a speech pathologist (Martin Palmer) and an educator-psychologist (Carl Delacato). Glenn explained, “Since we each knew our own fields, we proved to be treasure houses of knowledge for each other. We made an exciting, stimulating and productive combination. For the next ten or fifteen years we fed each other’s happy hunger for information.”

Glenn and his staff worked around the clock

Thanks to the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. A. Vinton Clarke, for whom Clarke Hall is named, Glenn was able to purchase Brookfield, an 8.4-acre estate in Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania. “Through his sister-in-law, Elizabeth Galbraith, the Clarkes provided the funding necessary to get us started. Jay Cooke, who was my regimental commander, used to own this property, and he sold it to us at a very affordable price,” explained Glenn. He and Katie left their home and moved to the Wyndmoor property, where their three children–Bruce, Janet, and Douglas–grew up in a new world of discovery. They were surrounded by families and brain-injured children on a regular basis and were honored to pitch in and help.

In 1962 The Rehabilitation Center at Philadelphia became The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, and Glenn served as the director until 1980, when his daughter, Janet, was named director.

In the early years, Glenn and his team traveled the globe to study children in remote areas and in the most cultured cities. They visited the Inuit children in the Arctic, Bushmen children in the Kalahari Desert, and Xingu children in Mato Grosso, Brazil, among others. Their mission was to observe and define the vital steps of human neurological development, in other words, what steps were critical to a child’s development and in what sequence they should occur.

Dr. Evan Thomas, Kalapalo Chieftain, and Glenn Doman in the Xingu territory in 1966

Thousands of man-hours went into their research, and the result is a unique tool that can be used to evaluate the neurological function of a child. Now known as The Institutes Developmental Profile, it outlines the six areas of function and the seven critical stages at which each function develops in a well child. The Developmental Profile can be used to precisely calculate a child’s neurological age and as a guide for providing sensory stimulation and motor opportunity to grow and develop the brain.

Years later, Glenn stated, “If The Institutes are remembered two hundred years from now, they will be best known for the Developmental Profile. It is really an astonishing instrument. It measures not only brain-injured children, but it measures all children against those six things that matter to man, that make man. They are the six intelligences of man—visual, auditory, tactile, mobility, language, and manual competence. And here is this simple instrument that anybody can see clearly and can measure any child in chronological terms and neurological terms. The difference between the chronological terms and neurological terms tells you either how hurt he is, or how average he is, or how far above average he is—which is a pretty important thing. It applies, of course, not only to children but applies to adults who can be measured.”

Amazingly, The Developmental Profile has not changed since its creation 55 years ago, but treatment procedures at The Institutes have evolved over time. As Glenn explained, “The most important discovery is always the most recent one. Every one of them has been a step higher than the previous one, a step more direct and a step more successful. And every time we make a new discovery, I think to myself, how could I have been such a meathead as to have not seen that before. If only we had known that a long time ago.

“In the beginning it was the floor program, then it was patterning, then masking. There was always crawling and creeping and walking, but I guess the next thing was brachiation—standing up and walking holding onto branches. Raymond Dart, the world’s leading anthropologist at the time, proposed to us that that was how man had first gotten up on his hind legs, and that’s how the kids do it now.

“Then I suppose it was the Respiratory Patterning and then the Oxygen Enrichment Program. There have been very important discoveries in nutrition that are helping hurt children to make significant progress more quickly on the program. Nutrition has been a very important part of our program since Adelle Davis first came to teach us in the early 1970s, but it is even more important today. Adelle herself would be proud of the progress that is being made in this area.

“Our first determination was that we were going to fix the kids, and we knew even then that in order to do that we had to fix the brain. And so everything we have done has been aimed directly at the brain. Everyone asked, how can you affect the brain since it is inside a solid skull?, but we pointed out that the brain is actually the easiest organ to affect. How do you affect the other organs? Even right now, you’re affecting my brain and I’m affecting yours.

Glenn always says the five most important words for parents “The Brain Grows By Use”

“Everything we do, even patterning, which looks like exercise but isn’t, except for the people doing the patterning, is aimed at the brain, saying, ‘This is how it feels to crawl.’ Now, when we take kids who can’t move but who have been patterned for a few years and put them into the gravity-free environment, they all go immediately into a cross pattern, because all that time the parents have put that into the brain, and out it comes.”

New programs continue to emerge, including elimination and rotation diets, neurofeedback and biofeedback, and heavy metal detoxification. But the staff does not simply design a program. They respectfully listen to the parents while doing a full history and evaluation, and teach them about child brain development in a series of lectures that are geared towards each group of parents. When it comes time to teach the parents the new home program, each staff member takes as long as necessary to make sure that the parents understand why and how to do each part of the program.

And what is Glenn’s opinion of those persistent, determined parents? Glenn has said, “Parents are not the problem with children, parents are the answer.”

Over a half-century Glenn and his ideas have been challenged and attacked, but always the parents and staff stood by his side. Glenn explained, “There was one time in my life when I was afraid The Institutes couldn’t make it. We had overcome such difficulties as no money, not enough help, not enough equipment, not sufficient room.

“All those were natural and usual problems. We had also withstood twenty years of attacks by all those chowderheads who, without thinking of the harm they were doing, tried to protect and maintain the status quo in the treatment of brain-injured children. However, when none of this worked, a large group of frightened organizations issued a public attack on us that was both untrue and libelous.

“Everyone but the parents attacked us. For a while it got a little rough. We had little left to us except our beliefs. We were almost pushed into considering the question of whether we could continue.

“But the staff here, that collection of absolute geniuses, without whom I could never have survived, stood like granite. The families of our brain-injured kids came to our defense and supported us in every way. We stuck together, and together with our parents we weathered the storm.”

Over the years, imitators of The Institutes work would come and go, usually diluting or altering that work and most of all the results but the Staff and families always persisted and stood strong. They demanded excellence for their children and they still do so today.

By the early 1960s Glenn and his staff were seeing the enormous learning potential of brain-injured children, some of whom were learning to read at an early age. They had to ask themselves, “What’s wrong with well kids?” When Glenn wrote his groundbreaking book How To Teach Your Baby To Read, he learned that mothers embraced the notion that they could teach their children to read. And it was great fun.

Glenn dubbed this sea change The Gentle Revolution, and in an essay with that title wrote: “It is possibly the most important of revolutions and surely the most glorious. Consider first the objective of the Gentle Revolution: to give all parents the knowledge required to make highly intelligent, extremely capable, and delightful children, and by so doing to make a highly humane, sane and decent world.”

Glenn, well into his seventies, still indefatigable

From there followed The Gentle Revolution Series of books guiding parents to teach their children math, encyclopedic knowledge, and physical development. These books, now in many languages, are today the most widely read books ion early development in the world. In other words, How To Multiply Your Baby’s Intelligence. The Evan Thomas Institute for Early Development and The How To Multiply Your Baby’s Intelligence course were born.

Likewise, the What To Do About Your Brain-Injured Child Course was created, and both courses are now taught around the world in different languages. Since the beginning, Glenn was a principle lecturer in both courses, and through video courses and lectures he continues to teach and inspire parents with his knowledge and wisdom.

When Glenn has given us an incredible legacy of search and discovery. He also left a staff dedicated to continuing his work. As Glenn once said, “Without any question my favorite people in the whole world are the staff of The Institutes. They are incredible and very wonderful, and I love every one of them. As for my second-favorite people—it would be hard to say whether it’s the kids or the parents. Maybe I can’t separate them, so I would have to say it’s the families.”

Glenn with his fellow kids at play

Today Glenn is remembered by his beloved staff, his beloved brothers in arms, and parents and children around the world. For all of us, Glenn Doman is a courageous leader, an extraordinary teacher, and our inspiration every day at his beloved Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential. We continue to fight the good fight for all

children both hurt and well – what an honor it is.

Donate

Donate