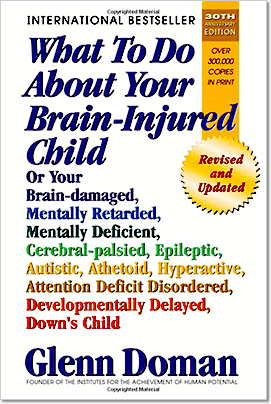

What Causes Brain Injury? Read An Excerpt From Our Founder’s Ground-Breaking Book “What To Do About Your Brain-Injured Child”

Brain injury is due to forces from outside the brain itself rather than to any inherent, pre-conceptual, built-in deficiency. We know of at least a hundred factors that can hurt a good brain subsequent to that instant of conception. There may be a thousand.

In point of fact, it is not terribly important how a brain got injured–what counts is how badly and where. Nevertheless, a brain can get hurt in so many ways that it may be worthwhile to review some of them, if only to show that it can happen to anybody.

Among the thousands of brain-injured children who come to The Institutes, we see, for example, the child whose mother and father have an incompatible Rh factor which sets up a blood incompatibility between mother and child. This hurts a good brain.

We see the child whose mother had German measles or some other such contagious disease during the first three months of her pregnancy, or even later in the pregnancy. This can hurt a good brain.

We see the child whose mother, during her pregnancy, goes through periods when she doesn’t get enough oxygen to supply both her needs and that of her baby’s.

When I went to school we were taught that if during pregnancy there was not enough of something to supply the needs of both mother and child, it would be mother rather than child who would suffer. Today we know that it is baby who will get too little. This hurts a good brain. We see the baby who is born prematurely and who is simply not “done” yet when he is ejected into the world. Babies rarely survive if born prior to the seventh prenatal month, but from the seventh month onward, each additional day makes survival more likely. Of all the factors that may be associated with brain injury, this factor of prematurity comes up most often in our case histories, in fact about three times as often as you would expect purely on the basis of chance. This does not, of course, mean that a premature baby will necessarily be brain-injured beyond the point that most of us are brain-injured.

We also see more than our share of post-mature babies. Apparently these babies are “too done” as it were, though again (as with most such conditions) the question of what is cause and what is effect is not easy to answer. It is possible that in some of these circumstances it is the brain injury that causes the post-maturity or the prematurity and not the other way round. Nonetheless, we very commonly see these factors associated with hurt children.

We see also the baby whose mother had large amounts of X-ray during pregnancy; even small amounts during the early days can apparently be harmful. Most radiography departments are reluctant to X-ray mothers during pregnancy, particularly during the early days of pregnancy, but this sometimes occurs when Mother is unaware that she is pregnant.

We see also more than our share of children who are born of a precipitous labor, by which we mean a labor lasting less than two hours, or of a protracted labor, by which we mean a labor lasting more than eighteen hours. If either factor is cause rather than effect, then possibly the baby needs a certain time in which to make the violent transition from womb to world–enough time but not too much.

Perhaps because the birth process itself is important, our share of children delivered by Cesarean section is about three times normal. Again there is the possibility that the child may have had to be delivered by Cesarean section because he was brain-injured rather than the other way around.

We see, tragically, the baby who is about to be born and whose birth is purposely delayed because the mother has not yet reached the doctor or the doctor has not yet reached the mother. Birth, in these cases we have seen, is generally delayed by having the mother sit up or cross her legs to prevent the baby being born. We have seen so many of these babies that we are completely persuaded that delaying the birth of a baby is a very bad idea. We are persuaded that any nurse, or perhaps even any father, can do a better job of delivering a baby than may result if the birth process is purposely delayed. A friend of ours was forced to stop en route to the hospital long enough to deliver his own wife of a fine baby in broad daylight in the crowded parking lot of a supermarket. Mother and baby did beautifully although Father remained somewhat shaken for a few days, it being his first delivery. We are persuaded that baby had a better chance of being the fine child it is than would have been the case if the birth had been significantly delayed.

We see also the baby who had obstetrical difficulties due to placenta previa, placenta abruptio, and other “technical” problems which create difficulties during the birth process. The baby may have been in a position which made his delivery either difficult or even impossible. In such cases, the baby must be manipulated before he can be delivered. In these cases also it is debatable whether the brain injury led to the problem or the problem led to the brain injury.

Long ago, when I went to school, we were given the impression that a high number of brain-injured children were a result of poor obstetrical practices. We have come to believe, however, that this is rare, and that only a very small number of brain-injured children are a result of bad obstetrics. Pre-existing factors in the child frequently make the delivery difficult, thus giving the impression of unnecessarily long delivery. The brain can also be injured after birth.

We see the infant who at two months of age falls out of a crib or bassinet, causing blood clots on the brain (which are called subdural hematomas), and this hurts a good brain.

We see the one-year-old who inhales certain insecticides, which can cause death or very severe brain injury. One of the most severely brain-injured children we have ever seen, who incidentally was one of our relatively small number of complete failures, had been a totally normal child until one year of age at which time he had ingested such an insecticide. We have seen other children, brain injured as a result of poisoning, who have done very well.

We see the four-year-old who falls in a swimming pool and dies of drowning, but who is then revived and who, during the short period of death, was not getting oxygen to his brain and who is brain-injured as a result.

We see the nine-year-old who, during surgery for tonsillitis or some other problem, sustains a cardiac arrest and dies on the operating table and is revived by open chest surgery and heart massage or some other technique but who during the time when his heart was not beating, like the child who drowned, did not get enough oxygen to the brain and who, as a result, had his good brain injured.

We see the twenty-year-old girl, who in the hours following the birth of her own baby, has a blood vessel rupture in her own brain giving mother, rather than baby, a stroke. If you have an idea that only old people have strokes, we can tell you that the youngest stroke case we ever saw at The Institutes was two months old and that the oldest stroke case we ever saw was 97 years old.

I should not like to leave the impression that young mothers often have strokes following birth. This is not common, but neither is it rare, and it is another way to hurt a good brain–in this case, Mother’s.

We see the twenty-year-old who, on the battlefield, gets a bullet through his brain, as did three friends of mine. All three managed to do well in life, even though they had millions of brain cells not only dead but gone-blown all over the battlefields of Germany and Korea and Belgium. Still it is not a good idea to get a bullet through the brain, and that’s another way to hurt a good brain.

We see the thirty-year-old who goes through the windshield in an automobile accident, and that’s another way to hurt a good brain.

We see the forty-year-old who has a brain tumor, and that’s another way to hurt a good brain.

We see the fifty-year-old who is assaulted with a blackjack in a robbery, and that’s another way to hurt a good brain.

We see the sixty-year-old who gets Parkinson’s disease, and that also hurts the brain.

We see the ninety-year-old who has literally billions, not merely millions, of cells dead for no better reason than the fact that he’s getting pretty old.

All the people described above, and many more, are truly brain-injured people, which is no more than to say that they have a good quality brain which has a great many dead cells.

But so, on the other hand, do I. It is just that at this moment in history I do not have as many.

by Glenn Doman, from What To Do About Your Brain-Injured Child

Donate

Donate