Parents Are Not the Problem: Parents Are the Answer

PARENTS ARE NOT THE PROBLEM:

PARENTS ARE THE ANSWER

When we human beings get a myth firmly planted in our minds, it becomes almost impossible to get it out. Such a myth can make us know what we’ re going to see before we see it. Then, no matter what actually happens, we see what we thought we were going to see. To put it differently, so much of what we “see” doesn’t start with the image sent by the eye to the brain, as it should, but starts instead within the brain. In the same way, so much of what we “hear“ isn’t what was sent by our ears to our brain, but is instead what we expected to hear. Professional people are by no means immune to such myths, and the greatest of all these professional myths is the one that maintains that, if it weren’t for parents, everything would be absolutely great in the world of children.

This myth so dearly loved by educators, special educators, psychologists, librarians, pediatricians, therapists and a host of others who deal with parents and children, just isn’t so. Parents are not the problem: Parents are the answer! The greater the number of problems a child has, and the more serious the problems, the more important this basic fact becomes. Parents are not the problem with children: Parents are the answer. I see this with crystal clarity at The Institutes in relation to fathers, whom I take as an example because I am a male.

During the intensive week which both parents and child spend with us at The Institutes (and which I described briefly in the very beginning of this book), we teach every father to do a complex program for his child and we make him reasonably competent. He will never do the program as competently as I do it for the simple reason that in all his life he will never do the program one tenth as much as I’ve done it.

But that doesn’t mean that I can treat his daughter Mary better than he can. He is her father and I am not. The combination of being reasonably competent and her father (which he is) is much more powerful than being highly competent and not her father (which I am not). I can make him reasonably competent, but he can’t make me her father, even a little bit.

What is true of her father is even more true of her mother.

And oh, what myths there are about mothers. Oh, what sly innuendoes and what outright lies, and what outrageous ones. The myths about mothers are so outrageous that they would be absolutely hilarious—if the consequences weren’t so tragic and disastrous.

The unspoken law holds that all mothers are idiots and they have no truth in them. The tragic consequence of this is that almost no professional people talk to mothers, and God knows that almost nobody listens to them. What makes this so especially sad is that mothers know more about their own children than anyone else in the world.

The myth says that the trouble with mothers is that they are too emotionally involved with their children. Now surely that suggests that somehow things would be better if mothers were not emotionally involved with their children. Have you ever thought what the world would be like if mothers were not emotionally involved with their children?

Every time I think of that, it occurs to me that I’m sure mother alligators are less emotionally involved with baby alligators than mother people are with baby people. But I wonder if that’s better for the baby alligators. Or is that maybe why they are baby alligators instead of baby people, because their mothers are not emotionally involved with them? The myth goes on to say that because mothers are emotionally involved with their children, they can’t be objective about them. I suppose if a mother has got a well kid she can afford her little myth that this kid is going to be President or the first lady pope or whatever. Why not? I suppose somebody is going to be, and who’s got a right to deny that this may be the one? If a mother has got a hurt kid, she can’t afford any myths, and nobody in the world knows it better than mother does.

Nobody in all of the world. But professionals insist that mothers don’t want to know if the children are hurt.

Let me tell you a story. Again, this would be highly amusing if it weren’t so tragic. In every hospital in the world, the instant a child is born, a struggle begins between the staff and the mother, with the mother making every effort to get her baby and the staff making every effort to prevent her from getting her baby. All mother wants is to get her hands on the baby, get the staff out of the room, strip the baby down to the buff and start counting. Five toes on this foot, five toes on this foot, two eyes, two ears, one nose. Now if mother doesn’t want to know, what the devil is the inventory for? Why has she taken it if the truth is that she doesn’t want to know? When we get smarter, the first thing we’ll do when a baby is born is give it to the mommy and say, “Here’s a check sheet. Please check off whether he’s got everything or not.” Did any reader who is a mother fail to take an inventory of her child as early as possible? Well now, if you didn’t want to know whether something was wrong, why were you counting?

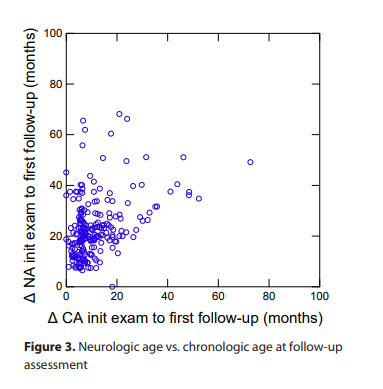

Now consider the next step. The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential have the most sophisticated records of brain-injured children in the world, the largest number of brain-injured children that were ever treated by a single system in history. Those records are very thorough. In the histories we take from the parents, among the hundreds of questions we ask are these three: (A) Who first decided this child had a problem? (B) When? (C) Why? If you go into our record room and take out a thousand charts and look up that question, in more than nine hundred out of a thousand charts it was mother who first decided the child had a problem, and generally she had a hell of a time convincing anybody else.

Here’s a typical case history of a severely brain-injured child, who was severely brain-injured from birth. (By the way, if it’s a moderately brain-injured child, same story; it just takes longer—three years. If it’s mildly brain-injured, it takes still longer—six years. Same story always.)

At three months of age, Mother says, “Doctor, there’s something wrong with my baby.” And the doctor says, “All mothers think that.” At six months of age, Mother says, “Doctor, there’s something wrong with my baby.” And he says, “Don’t compare one baby to another; they’re all different from each other.” At nine months of age, Mother’s voice is going up. It has a slight edge of hysteria, not because she knows she’s got a hurt child, but because nobody will listen to her. And she says, “Doctor, there’s something wrong with my baby!” And he says, “He’s a little slow, but he’ll grow out of it.” At eighteen months of age, Mother says (she’s very calm now, she’s made up her mind), “Doctor, are you going to do something about my baby or am I going to get another doctor?” And that’s the day the doctor discovers severely brain-injured children. That very day. And then an astonishing thing happens: He says, “Not only is something wrong with your baby, but he is hopeless.”

Now the question is, what changed that day? Did the baby actually go from being totally normal to totally hopeless in one day? Did Mother change? That’s what she’s been saying all along. Only one thing changed that day—the professional mind. And then these emotionally involved, fool mothers say an interesting thing; they say, “Doctor, for eighteen months I’ve been telling you something was wrong and you’ve been saying it wasn’t, and you were wrong. Now you’re saying he’s hopeless—and you’re wrong again.”

The myth goes on to say that the problem with mothers is that they’re not objective about their children, that they’re unrealistic. And then it goes on to describe this unrealistic mother. I have learned that mothers of brain-injured children are so realistic they scare me. They’ve been laughed at by professionals so long that they’re afraid to say anything hopeful about the child for fear they’ll be laughed at again, and the consequence of that is that every once in a while I see a little three-year-old kid and I say, “Does he understand the word ‘Mommy’? And Mother says, “Well now I can’t prove it . . .” and I say, “Now look, Mom, he’s not taking college board entrance requirements, I just want to know if you think he understands ‘Mommy’ or not.” There’s nobody more realistic than mothers of brain-injured children.

That unrealistic mother—I do see her every once in a while. It isn’t that she doesn’t exist, she exists all right. And when I see her she’s exactly as painted. She brings in a little three-year old lump and puts him on my floor. He can’t move, he can’t make sounds and she tells me about how he can walk and talk. And I have found my unrealistic mother. The only thing is, I’ve been led to believe that she’s unrealistic because she’s got a brain-injured child. When I find this gal—she’s unrealistic about everything. She’s simply an unrealistic human being who happens to be the mother of a brain-injured child.

I mean, there’s nothing about being unrealistic that keeps you from being pregnant, is there? Indeed, there may be some things about being unrealistic that lead to pregnancy. It’s quite possible for unrealistic people to become mothers and so, when I find her, she’s just exactly as painted. What is lied about is not what she’s like; it’s her frequency. Because I’m told she’s everybody. And I see her regularly . . . every three years. She’s one in a thousands mothers.

As I said earlier: Parents are not the problem with children: Parents are the answer.

All over the world today, a sad, sad drama is being acted out. All over the world parents are taking their brain-injured children to institutions for what is solemnly called “Evaluation and Diagnosis.”

Such evaluations are generally extremely expensive and require the child to be an inpatient for ten days or two weeks. At the end of this period of time it is quite possible for the parents (if they are unlucky) to get back the child and a large bill without anybody even saying good-bye to them. This approach suggests that children exist for the purpose of being evaluated. It is a quaint view of life.

If the parents are luckier, at the end of the child’s hospitalization, in addition to receiving the child and the large bill, somebody says good-bye to them, which generally means that someone sits down with them and explains that they have done this test and this test and this test. The conversation then goes like this:

Parents: “Yes?”

Pro: “As a consequence of all these tests we have diagnosed your child as ‘Severely Mentally Retarded.’”

Parents: “Yes?”

Pro: “Well that’s it. Your child is severely mentally retarded.”

Parents: “But what does that mean?”

Pro: “Why that means your son can’t do what other children his age can do.”

Dad: (After a long silence) “You’re pulling my leg. You have to be. You wouldn’t dare bring my child in here and keep him ten days and do painful things to him and then give us a large bill and dare to tell us that he can’t do the things that other kids his age can do. Why that’s exactly what we told you when we brought him here. We don’t need to pay anybody to tell us what he can’t do. His mother here is the world’s leading authority on what he can’t do—and what he can do. That’s all we’ve talked about every night for the last four years. You’re joking, and it’s a damned bad joke.”

Pro: “No, I’m not joking. I’ve been in this field for five years and I’m telling you your son is severely mentally retarded and you better face up to it.”

Parent: “We didn’t bring our son here to be told what he can’t do, and we didn’t bring him here to have you put a name on not being able to do what other kids his age do.

“We brought him here to find out two things. First: Why he can’t do what other kids do, and Second: What we’ re going to do about it. If you can’t tell us the answer to these questions, we’ll look until we find somebody who can.”

And, as usual with parents, they are the two exactly proper questions that must be answered if we’ re going to solve the problems of brain-injured children.

As I think I mentioned before, Parents are not the problem with children: Parents are the answer. It took me a very long time to learn this in the face of all the myths I lived with, but I finally learned it.

Most people think that the reason we teach parents to program their children instead of doing it ourselves is because it is so much cheaper for parents.

Certainly it is true that it would cost huge sums of money if we were going to actually treat the kids seven days a week for eight, ten or twelve hours a day as the parents do. But that’s not why we have the parents treat the children.

The reason is that we know without question that if parents are taught thoroughly what is going on and why we do what we do and precisely how to do it, then the simple fact is that parents can do it better than we can do it. Better than Glenn Doman. Better than Hazel Doman. Better than Gretchen Kerr. Better than Elaine Lee. Better than Roselise Wilkinson. Better than Suzy Aisen. Better than Ann Ball.

The reason that parents can treat kids better than we can, if they know what they’re doing, is very simple.

Much as everyone on the staff loves brain-injured children, and love them they do, each individual kid is loved even more by his individual parents.

Parents are not the problem with brain-injured children: Parents are the answer.

Donate

Donate